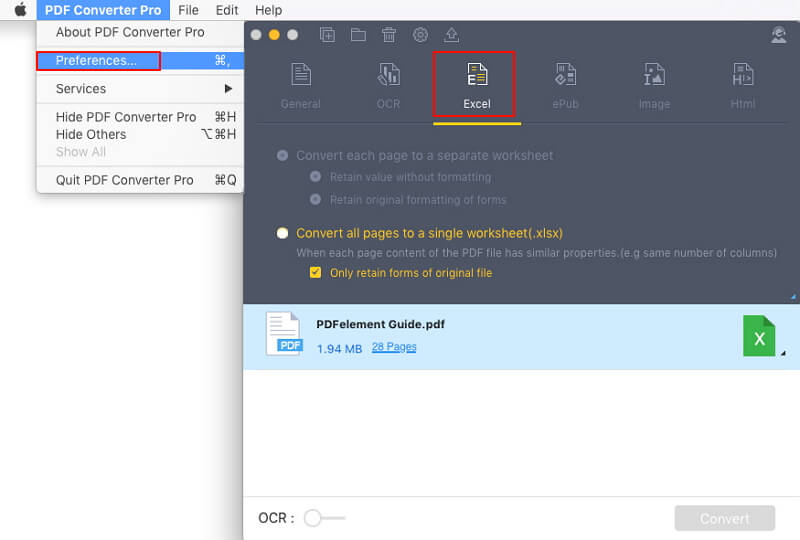

- Open Excel Mac Manual Calculation Mode Excel

- Excel Manual Calculation Shortcut

- Excel Calculation Mode Automatic

- Excel Calculation Options Manual

- Open Excel Mac Manual Calculation Mode 2017

- Excel Calculation Changes To Manual

- Macbook Manual

Nov 27, 2008 Re: open excel in calculation manual. The calculation setting is determined by the first opened file within Excel (with Automatic being the default). The easiest way to ensure calculation is set to manual is to create or find your Personal.xls macro workbook, unhide it (WindowUnhide) and use ToolsOptions to amend to Manual Calculation.

-->As far as I know, if you open an Excel file and set the calculation mode to Automatic, then open another Excel file that has been saved in Manual mode, it will NOT change to Automatic mode. Conversely, if you open an Excel file that has been saved in Manual mode, then open another Excel file saved in Automatic mode, it will CHANGE to Manual mode. Apr 29, 2016 The Excel Options dialog box displays. Click “Formulas” in the list of items on the left. In the Calculation options section, click the “Manual” radio button to turn on the ability to manually calculate each worksheet. When you select “Manual”, the “Recalculate workbook before saving” check box is automatically checked. Apr 17, 2018 How to change the mode of calculation in Excel. To change the mode of calculation in Excel, follow these steps: Click the Microsoft Office Button, and then click Excel Options. On the Formulas tab, select the calculation mode that you want to use. Jul 17, 2017 The calculation mode is most often set based on the calculation mode of the first workbook opened in the Excel session. Each Excel workbook contains the setting of the calculation mode at the point it saves. The Excel application will adopt that calculation mode if it is the first workbook opened in a session.

Applies to: Excel | Excel 2013 | Excel 2016 | VBA

The 'Big Grid' of 1 million rows and 16,000 columns in Office Excel 2016, together with many other limit increases, greatly increases the size of worksheets that you can build compared to earlier versions of Excel. A single worksheet in Excel can now contain over 1,000 times as many cells as earlier versions.

In earlier versions of Excel, many people created slow-calculating worksheets, and larger worksheets usually calculate more slowly than smaller ones. With the introduction of the 'Big Grid' in Excel 2007, performance really matters. Slow calculation and data manipulation tasks such as sorting and filtering make it more difficult for users to concentrate on the task at hand, and lack of concentration increases errors.

Recent Excel versions introduced several features to help you handle this capacity increase, such as the ability to use more than one processor at a time for calculations and common data set operations like refresh, sorting, and opening workbooks. Multithreaded calculation can substantially reduce worksheet calculation time. However, the most important factor that influences Excel calculation speed is still the way your worksheet is designed and built.

You can modify most slow-calculating worksheets to calculate tens, hundreds, or even thousands of times faster. By identifying, measuring, and then improving the calculation obstructions in your worksheets, you can speed up calculation.

The importance of calculation speed

Poor calculation speed affects productivity and increases user error. User productivity and the ability to focus on a task deteriorates as response time lengthens.

Excel has two main calculation modes that let you control when calculation occurs:

Automatic calculation - Formulas are automatically recalculated when you make a change.

Manual calculation - Formulas are recalculated only when you request it (for example, by pressing F9).

For calculation times of less than about a tenth of a second, users feel that the system is responding instantly. They can use automatic calculation even when they enter data.

Between a tenth of a second and one second, users can successfully keep a train of thought going, although they will notice the response time delay.

As calculation time increases (usually between 1 and 10 seconds), users must switch to manual calculation when they enter data. User errors and annoyance levels start to increase, especially for repetitive tasks, and it becomes difficult to maintain a train of thought.

For calculation times greater than 10 seconds, users become impatient and usually switch to other tasks while they wait. This can cause problems when the calculation is one of a sequence of tasks and the user loses track.

Understanding calculation methods in Excel

To improve the calculation performance in Excel, you must understand both the available calculation methods and how to control them.

Full calculation and recalculation dependencies

The smart recalculation engine in Excel tries to minimize calculation time by continuously tracking both the precedents and dependencies for each formula (the cells referenced by the formula) and any changes that were made since the last calculation. At the next recalculation, Excel recalculates only the following:

Cells, formulas, values, or names that have changed or are flagged as needing recalculation.

Cells dependent on other cells, formulas, names, or values that need recalculation.

Volatile functions and visible conditional formats.

Excel continues calculating cells that depend on previously calculated cells even if the value of the previously calculated cell does not change when it is calculated.

Because you change only part of the input data or a few formulas between calculations in most cases, this smart recalculation usually takes only a fraction of the time that a full calculation of all the formulas would take.

In manual calculation mode, you can trigger this smart recalculation by pressing F9. You can force a full calculation of all the formulas by pressing Ctrl+Alt+F9, or you can force a complete rebuild of the dependencies and a full calculation by pressing Shift+Ctrl+Alt+F9.

Calculation process

Open Excel Mac Manual Calculation Mode Excel

Excel formulas that reference other cells can be put before or after the referenced cells (forward referencing or backward referencing). This is because Excel does not calculate cells in a fixed order, or by row or column. Instead, Excel dynamically determines the calculation sequence based on a list of all the formulas to calculate (the calculation chain) and the dependency information about each formula.

Excel has distinct calculation phases:

Build the initial calculation chain and determine where to begin calculating. This phase occurs when the workbook is loaded into memory.

Track dependencies, flag cells as uncalculated, and update the calculation chain. This phase executes at each cell entry or change, even in manual calculation mode. Ordinarily this executes so fast that you do not notice it, but in complex cases, response can be slow.

Calculate all formulas. As a part of the calculation process, Excel reorders and restructures the calculation chain to optimize future recalculations.

Update the visible parts of the Excel windows.

The third phase executes at each calculation or recalculation. Excel tries to calculate each formula in the calculation chain in turn, but if a formula depends on one or more formulas that have not yet been calculated, the formula is sent down the chain to be calculated again later. This means that a formula can be calculated multiple times per recalculation.

The second time that you calculate a workbook is often significantly faster than the first time. This occurs for several reasons:

Excel usually recalculates only cells that have changed, and their dependents.

Excel stores and reuses the most recent calculation sequence so that it can save most of the time used to determine the calculation sequence.

With multiple core computers, Excel tries to optimize the way the calculations are spread across the cores based on the results of the previous calculation.

In an Excel session, both Windows and Excel cache recently used data and programs for faster access.

Calculating workbooks, worksheets, and ranges

You can control what is calculated by using the different Excel calculation methods.

Calculate all open workbooks

Each recalculation and full calculation calculates all the workbooks that are currently open, resolves any dependencies within and between workbooks and worksheets, and resets all previously uncalculated (dirty) cells as calculated.

Calculate selected worksheets

You can also recalculate only the selected worksheets by using Shift+F9. This does not resolve any dependencies between worksheets, and does not reset dirty cells as calculated.

Calculate a range of cells

Excel also allows for the calculation of a range of cells by using the Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) methods Range.CalculateRowMajorOrder and Range.Calculate:

Range.CalculateRowMajorOrder calculates the range left to right and top to bottom, ignoring all dependencies.

Range.Calculate calculates the range resolving all dependencies within the range.

Because CalculateRowMajorOrder does not resolve any dependencies within the range that is being calculated, it is usually significantly faster than Range.Calculate. However, it should be used with care because it may not give the same results as Range.Calculate.

Range.Calculate is one of the most useful tools in Excel for performance optimization because you can use it to time and compare the calculation speed of different formulas.

For more information, see Excel performance: Performance and limit improvements.

Volatile functions

A volatile function is always recalculated at each recalculation even if it does not seem to have any changed precedents. Using many volatile functions slows down each recalculation, but it makes no difference to a full calculation. You can make a user-defined function volatile by including Application.Volatile in the function code.

Some of the built-in functions in Excel are obviously volatile: RAND(), NOW(), TODAY(). Others are less obviously volatile: OFFSET(), CELL(), INDIRECT(), INFO().

Some functions that have previously been documented as volatile are not in fact volatile: INDEX(), ROWS(), COLUMNS(), AREAS().

Volatile actions

Volatile actions are actions that trigger a recalculation, and include the following:

- Clicking a row or column divider when in automatic mode.

- Inserting or deleting rows, columns, or cells on a sheet.

- Adding, changing, or deleting defined names.

- Renaming worksheets or changing worksheet position when in automatic mode.

- Filtering, hiding, or un-hiding rows.

- Opening a workbook when in automatic mode. If the workbook was last calculated by a different version of Excel, opening the workbook usually results in a full calculation.

- Saving a workbook in manual mode if the Calculate before Save option is selected.

Formula and name evaluation circumstances

A formula or part of a formula is immediately evaluated (calculated), even in manual calculation mode, when you do one of the following:

- Enter or edit the formula.

- Enter or edit the formula by using the Function Wizard.

- Enter the formula as an argument in the Function Wizard.

- Select the formula in the formula bar and press F9 (press Esc to undo and revert to the formula), or click Evaluate Formula.

A formula is flagged as uncalculated when it refers to (depends on) a cell or formula that has one of these conditions:

- It was entered.

- It was changed.

- It is in an AutoFilter list, and the criteria drop-down list was enabled.

- It is flagged as uncalculated.

Excel Manual Calculation Shortcut

A formula that is flagged as uncalculated is evaluated when the worksheet, workbook, or Excel instance that contains it is calculated or recalculated.

The circumstances that cause a defined name to be evaluated differ from those for a formula in a cell:

- A defined name is evaluated every time that a formula that refers to it is evaluated so that using a name in multiple formulas can cause the name to be evaluated multiple times.

- Names that are not referred to by any formula are not calculated even by a full calculation.

Data tables

Excel data tables (Data tab > Data Tools group > What-If Analysis > Data Table) should not be confused with the table feature (Home tab > Styles group > Format as Table, or, Insert tab > Tables group > Table). Excel data tables do multiple recalculations of the workbook, each driven by the different values in the table. Excel first calculates the workbook normally. For each pair of row and column values, it then substitutes the values, does a single-threaded recalculation, and stores the results in the data table.

Data table recalculation always uses only a single processor.

Data tables give you a convenient way to calculate multiple variations and view and compare the results of the variations. Use the Automatic except Tables calculation option to stop Excel from automatically triggering the multiple calculations at each calculation, but still calculate all dependent formulas except tables.

Controlling calculation options

Excel has a range of options that enable you to control the way it calculates. You can change the most frequently used options in Excel by using the Calculation group on the Formulas tab on the Ribbon.

Figure 1. Calculation group on the Formulas tab

To see more Excel calculation options, on the File tab, click Options. In the Excel Options dialog box, click the Formulas tab.

Figure 2. Calculation options on the Formulas tab in Excel Options

Many calculation options (Automatic, Automatic except for data tables, Manual, Recalculate workbook before saving) and the iteration settings (Enable iterative calculation, Maximum Iterations, Maximum Change) operate at the application level instead of at the workbook level (they are the same for all open workbooks).

To find advanced calculation options, on the File tab, click Options. In the Excel Options dialog box, click Advanced. Under the Formulas section, set calculation options.

Figure 3. Advanced calculation options

When you start Excel, or when it is running without any workbooks open, the initial calculation mode and iteration settings are set from the first non-template, non-add-in workbook that you open. This means that the calculation settings in workbooks opened later are ignored, although, of course, you can manually change the settings in Excel at any time. When you save a workbook, the current calculation settings are stored in the workbook.

Automatic calculation

Automatic calculation mode means that Excel automatically recalculates all open workbooks at every change and when you open a workbook. Usually when you open a workbook in automatic mode and Excel recalculates, you do not see the recalculation because nothing has changed since the workbook was saved.

You might notice this calculation when you open a workbook in a later version of Excel than you used the last time that the workbook was calculated (for example, Excel 2016 versus Excel 2013). Because the Excel calculation engines are different, Excel performs a full calculation when it opens a workbook that was saved using an earlier version of Excel.

Manual calculation

Manual calculation mode means that Excel recalculates all open workbooks only when you request it by pressing F9 or Ctrl+Alt+F9, or when you save a workbook. For workbooks that take more than a fraction of a second to recalculate, you must set calculation to manual mode to avoid a delay when you make changes.

Excel tells you when a workbook in manual mode needs recalculation by displaying Calculate in the status bar. The status bar also displays Calculate if your workbook contains circular references and the iteration option is selected.

Iteration settings

If you have intentional circular references in your workbook, the iteration settings enable you to control the maximum number of times the workbook is recalculated (iterations) and the convergence criteria (maximum change: when to stop). Clear the iteration box so that if you have accidental circular references, Excel will warn you and will not try to solve them.

Workbook ForceFullCalculation property

When you set this workbook property to True, Excel's Smart Recalculation is turned off and every recalculation recalculates all the formulas in all the open workbooks. For some complex workbooks, the time taken to build and maintain the dependency trees needed for Smart Recalculation is larger than the time saved by Smart Recalculation.

If your workbook takes an excessively long time to open, or making small changes takes a long time even in manual calculation mode, it may be worth trying ForceFullCalculation.

Calculate will appear in the status bar if the workbook ForceFullCalculation property has been set to True.

You can control this setting using the VBE (Alt+F11), selecting ThisWorkbook in the Project Explorer (Ctrl+R) and showing the Properties Window (F4).

Figure 4. Setting the Workbook.ForceFullCalculation property

Making workbooks calculate faster

Use the following steps and methods to make your workbooks calculate faster.

Processor speed and multiple cores

For most versions of Excel, a faster processor will, of course, enable faster Excel calculation. The multithreaded calculation engine introduced in Excel 2007 enables Excel to make excellent use of multiprocessor systems, and you can expect significant performance gains with most workbooks.

For most large workbooks, the calculation performance gains from multiple processors scale almost linearly with the number of physical processors. However, hyper-threading of physical processors only produces a small performance gain.

For more information, see Excel performance: Performance and limit improvements.

RAM

Paging to a virtual-memory paging file is slow. You must have enough physical RAM for the operating system, Excel, and your workbooks. If you have more than occasional hard disk activity during calculation, and you are not running user-defined functions that trigger disk activity, you need more RAM.

As mentioned, recent versions of Excel can make effective use of large amounts of memory, and the 32-bit version of Excel 2007 and Excel 2010 can handle a single workbook or a combination of workbooks using up to 2 GB of memory.

The 32-bit versions of Excel 2013 and Excel 2016 that use the Large Address Aware (LAA) feature can use up to 3 or 4 GB of memory, depending on the version of Windows installed. The 64-bit version of Excel can handle larger workbooks. For more information, see the 'Large data sets, LAA, and 64-bit Excel' section in Excel performance: Performance and limit improvements.

A rough guideline for efficient calculation is to have enough RAM to hold the largest set of workbooks that you need to have open at the same time, plus 1 to 2 GB for Excel and the operating system, plus additional RAM for any other running applications.

Measuring calculation time

To make workbooks calculate faster, you must be able to accurately measure calculation time. You need a timer that is faster and more accurate than the VBA Time function. The MICROTIMER() function shown in the following code example uses Windows API calls to the system high-resolution timer. It can measure time intervals down to small numbers of microseconds. Be aware that because Windows is a multitasking operating system, and because the second time that you calculate something, it may be faster than the first time, the times that you get usually do not repeat exactly. To achieve the best accuracy, measure time calculation tasks several times and average the results.

For more information about how the Visual Basic Editor can significantly affect VBA user-defined function performance, see the 'Faster VBA user-defined functions' section in Excel performance: Tips for optimizing performance obstructions.

To measure calculation time, you must call the appropriate calculation method. These subroutines give you calculation time for a range, recalculation time for a sheet or all open workbooks, or full calculation time for all open workbooks.

Copy all these subroutines and functions into a standard VBA module. To open the VBA editor, press Alt+F11. On the Insert menu, select Module, and then copy the code into the module.

To run the subroutines in Excel, press Alt+F8. Select the subroutine you want, and then click Run.

Figure 5. The Excel Macro window showing the calculation timers

Finding and prioritizing calculation obstructions

Most slow-calculating workbooks have only a few problem areas or obstructions that consume most of the calculation time. If you do not already know where they are, use the drill-down approach outlined in this section to find them. If you do know where they are, you must measure the calculation time that is used by each obstruction so that you can prioritize your work to remove them.

Drill-down approach to finding obstructions

The drill-down approach starts by timing the calculation of the workbook, the calculation of each worksheet, and the blocks of formulas on slow-calculating sheets. Do each step in order and note the calculation times.

To find obstructions using the drill-down approach

Ensure that you have only one workbook open and no other tasks are running.

Set calculation to manual.

Make a backup copy of the workbook.

Open the workbook that contains the Calculation Timers macros, or add them to the workbook.

Check the used range by pressing Ctrl+End on each worksheet in turn.

This shows where the last used cell is. If this is beyond where you expect it to be, consider deleting the excess columns and rows and saving the workbook. For more information, see the 'Minimizing the used range' section in Excel performance: Tips for optimizing performance obstructions.

Run the FullCalcTimer macro.

The time to calculate all the formulas in the workbook is usually the worst-case time.

Run the RecalcTimer macro.

A recalculation immediately after a full calculation usually gives you the best-case time.

Calculate workbook volatility as the ratio of recalculation time to full calculation time.

This measures the extent to which volatile formulas and the evaluation of the calculation chain are obstructions.

Activate each sheet and run the SheetTimer macro in turn.

Because you just recalculated the workbook, this gives you the recalculate time for each worksheet. This should enable you to determine which ones are the problem worksheets.

Run the RangeTimer macro on selected blocks of formulas.

For each problem worksheet, divide the columns or rows into a small number of blocks.

Select each block in turn, and then run the RangeTimer macro on the block.

If necessary, drill down further by subdividing each block into a smaller number of blocks.

Prioritize the obstructions.

Speeding up calculations and reducing obstructions

It is not the number of formulas or the size of a workbook that consumes the calculation time. It is the number of cell references and calculation operations, and the efficiency of the functions being used.

Because most worksheets are constructed by copying formulas that contain a mixture of absolute and relative references, they usually contain a large number of formulas that contain repeated or duplicated calculations and references.

Avoid complex mega-formulas and array formulas. In general, it is better to have more rows and columns and fewer complex calculations. This gives both the smart recalculation and the multithreaded calculation in Excel a better opportunity to optimize the calculations. It is also easier to understand and debug. The following are a few rules to help you speed up workbook calculations.

First rule: Remove duplicated, repeated, and unnecessary calculations

Look for duplicated, repeated, and unnecessary calculations, and figure out approximately how many cell references and calculations are required for Excel to calculate the result for this obstruction. Think how you might obtain the same result with fewer references and calculations.

Usually this involves one or more of the following steps:

Reduce the number of references in each formula.

Move the repeated calculations to one or more helper cells, and then reference the helper cells from the original formulas.

Use additional rows and columns to calculate and store intermediate results once so that you can reuse them in other formulas.

Second rule: Use the most efficient function possible

When you find an obstruction that involves a function or array formulas, determine whether there is a more efficient way to achieve the same result. For example:

Lookups on sorted data can be tens or hundreds of times more efficient than lookups on unsorted data.

VBA user-defined functions are usually slower than the built-in functions in Excel (although carefully written VBA functions can be fast).

Minimize the number of used cells in functions like SUM and SUMIF. Calculation time is proportional to the number of used cells (unused cells are ignored).

Consider replacing slow array formulas with user-defined functions.

Third rule: Make good use of smart recalculation and multithreaded calculation

The better use you make of smart recalculation and multithreaded calculation in Excel, the less processing has to be done every time that Excel recalculates, so:

Avoid volatile functions such as INDIRECT and OFFSET where you can, unless they are significantly more efficient than the alternatives. (Well-designed use of OFFSET is often fast.)

Minimize the size of the ranges that you are using in array formulas and functions.

Break array formulas and mega-formulas out into separate helper columns and rows.

Avoid single-threaded functions:

- PHONETIC

- CELL when either the 'format' or 'address' argument is used

- INDIRECT

- GETPIVOTDATA

- CUBEMEMBER

- CUBEVALUE

- CUBEMEMBERPROPERTY

- CUBESET

- CUBERANKEDMEMBER

- CUBEKPIMEMBER

- CUBESETCOUNT

- ADDRESS where the fifth parameter (the sheet_name) is given

- Any database function (DSUM, DAVERAGE, and so on) that refers to a PivotTable

- ERROR.TYPE

- HYPERLINK

- VBA and COM add-in user-defined functions

Avoid iterative use of data tables and circular references: both of these always calculate single-threaded.

Fourth rule: Time and test each change

Some of the changes that you make might surprise you, either by not giving the answer that you thought they would, or by calculating more slowly than you expected. Therefore, you should time and test each change, as follows:

Time the formula that you want to change by using the RangeTimer macro.

Make the change.

Time the changed formula by using the RangeTimer macro.

Check that the changed formula still gives the correct answer.

Rule examples

The following sections provide examples of how to use the rules to speed up calculation.

Period-to-date sums

For example, you need to calculate the period-to-date sums of a column that contains 2,000 numbers. Assume that column A contains the numbers, and that column B and column C should contain the period-to-date totals.

You could write the formula using SUM, which is an efficient function.

Figure 6. Example of period-to-date SUM formulas

Copy the formula down to B2000.

How many cell references are added up by SUM in total? B1 refers to one cell, and B2000 refers to 2,000 cells. The average is 1,000 references per cell, so the total number of references is 2 million. Selecting the 2,000 formulas and using the RangeTimer macro shows you that the 2,000 formulas in column B calculate in 80 milliseconds. Most of these calculations are duplicated many times: SUM adds A1 to A2 in each formula from B2:B2000.

You can eliminate this duplication if you write the formulas as follows.

Copy this formula down to C2000.

Now how many cell references are added up in total? Each formula, except the first formula, uses two cell references. Therefore, the total is 1999*2+1=3999. This is a factor of 500 fewer cell references.

RangeTimer indicates that the 2,000 formulas in column C calculate in 3.7 milliseconds compared to the 80 milliseconds for column B. This change has a performance improvement factor of only 80/3.7=22 instead of 500 because there is a small overhead per formula.

Error handling

If you have a calculation-intensive formula where you want the result to be shown as zero if there is an error (this frequently occurs with exact match lookups), you can write this in several ways.

You can write it as a single formula, which is slow:

B1=IF(ISERROR(time expensive formula),0,time expensive formula)You can write it as two formulas, which is fast:

A1=time expensive formulaB1=IF(ISERROR(A1),0,A1)Or you can use the IFERROR function, which is designed to be fast and simple, and is a single formula:

B1=IFERROR(time expensive formula,0)

Dynamic count unique

Figure 7. Example list of data for count unique

If you have a list of 11,000 rows of data in column A, which frequently changes, and you need a formula that dynamically calculates the number of unique items in the list, ignoring blanks, following are several possible solutions.

Array formulas (use Ctrl+Shift+Enter); RangeTimer indicates that this takes 13.8 seconds.

SUMPRODUCT usually calculates faster than an equivalent array formula. This formula takes 10.0 seconds, and gives an improvement factor of 13.8/10.0=1.38, which is better, but not good enough.

User-defined functions. The following code example shows a VBA user-defined function that uses the fact that the index to a collection must be unique. For an explanation of some techniques that are used, see the section about user-defined functions in the 'Using functions efficiently' section in Excel performance: Tips for optimizing performance obstructions. This formula,

=COUNTU(A2:A11000), takes only 0.061 seconds. This gives an improvement factor of 13.8/0.061=226.Adding a column of formulas. If you look at the previous sample of the data, you can see that it is sorted (Excel takes 0.5 seconds to sort the 11,000 rows). You can exploit this by adding a column of formulas that checks if the data in this row is the same as the data in the previous row. If it is different, the formula returns 1. Otherwise, it returns 0.

Add this formula to cell B2.

Copy the formula, and then add a formula to add up column B.

A full calculation of all these formulas takes 0.027 seconds. This gives an improvement factor of 13.8/0.027=511.

Excel Calculation Mode Automatic

Conclusion

Excel enables you to effectively manage much larger worksheets, and it provides significant improvements in calculation speed compared with early versions. When you create large worksheets, it is easy to build them in a way that causes them to calculate slowly. Slow-calculating worksheets increase errors because users find it difficult to maintain concentration while calculation is occurring.

By using a straightforward set of techniques, you can speed up most slow-calculating worksheets by a factor of 10 or 100. You can also apply these techniques as you design and create worksheets to ensure that they calculate quickly.

See also

Support and feedback

Have questions or feedback about Office VBA or this documentation? Please see Office VBA support and feedback for guidance about the ways you can receive support and provide feedback.

-->Applies to: Excel 2013 | Office 2013 | Visual Studio

The user can trigger recalculation in Microsoft Excel in several ways, for example:

Entering new data (if Excel is in Automatic recalculation mode, described later in this topic).

Explicitly instructing Excel to recalculate all or part of a workbook.

Deleting or inserting a row or column.

Saving a workbook while the Recalculate before save option is set.

Performing certain Autofilter actions.

Double-clicking a row or column divider (in Automatic calculation mode).

Adding, editing, or deleting a defined name.

Renaming a worksheet.

Changing the position of a worksheet in relation to other worksheets.

Hiding or unhiding rows, but not columns.

Note

This topic does not distinguish between the user directly pressing a key or clicking the mouse, and those tasks being done by a command or macro. The user runs the command, or does something to cause the command to run so that it is still considered a user action. Therefore the phrase 'the user' also means 'the user, or a command or process started by the user.'

Dependence, Dirty Cells, and Recalculated Cells

The calculation of worksheets in Excel can be viewed as a three-stage process:

Construction of a dependency tree

Construction of a calculation chain

Recalculation of cells

The dependency tree informs Excel about which cells depend on which others, or equivalently, which cells are precedents for which others. From this tree, Excel constructs a calculation chain. The calculation chain lists all the cells that contain formulas in the order in which they should be calculated. During recalculation, Excel revises this chain if it comes across a formula that depends on a cell that has not yet been calculated. In this case, the cell that is being calculated and its dependents are moved down the chain. For this reason, calculation times can often improve in a worksheet that has just been opened in the first few calculation cycles.

When a structural change is made to a workbook, for example, when a new formula is entered, Excel reconstructs the dependency tree and calculation chain. When new data or new formulas are entered, Excel marks all the cells that depend on that new data as needing recalculation. Cells that are marked in this way are known as dirty . All direct and indirect dependents are marked as dirty so that if B1 depends on A1, and C1 depends on B1, when A1 is changed, both B1 and C1 are marked as dirty.

If a cell depends, directly or indirectly, on itself, Excel detects the circular reference and warns the user. This is usually an error condition that the user must fix, and Excel provides very helpful graphical and navigational tools to help the user to find the source of the circular dependency. In some cases, you might deliberately want this condition to exist. For example, you might want to run an iterative calculation where the starting point for the next iteration is the result of the previous iteration. Excel supports control of iterative calculations through the calculation options dialog box.

After marking cells as dirty, when a recalculation is next done, Excel reevaluates the contents of each dirty cell in the order dictated by the calculation chain. In the example given earlier, this means B1 is first, and then C1. This recalculation occurs immediately after Excel finishes marking cells as dirty if the recalculation mode is automatic; otherwise, it occurs later.

Starting in Microsoft Excel 2002, the Range object in Microsoft Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) supports a method, Range.Dirty, which marks cells as needing calculation. When it is used together with the Range.Calculate method (see next section), it enables forced recalculation of cells in a given range. This is useful when you are performing a limited calculation during a macro, where the calculation mode is set to manual, to avoid the overhead of calculating cells unrelated to the macro function. Range calculation methods are not available through the C API.

In Excel 2002 and earlier versions, Excel built a calculation chain for each worksheet in each open workbook. This resulted in some complexity in the way links between worksheets were handled, and required some care to ensure efficient recalculation. In particular, in Excel 2000, you should minimize cross-worksheet dependencies and name worksheets in alphabetical order so that sheets that depend on other sheets come alphabetically after the sheets they depend on.

In Excel 2007, the logic was improved to enable recalculation on multiple threads so that sections of the calculation chain are not interdependent and can be calculated at the same time. You can configure Excel to use multiple threads on a single processor computer, or a single thread on a multi-processor or multi-core computer.

Asynchronous User Defined Functions (UDFs)

Excel Calculation Options Manual

When a calculation encounters an asynchronous UDF, it saves the state of the current formula, starts the UDF and continues evaluating the rest of the cells. When the calculation finishes evaluating the cells Excel waits for the asynchronous functions to complete if there are still asynchronous functions running. As each asynchronous function reports results, Excel finishes the formula, and then runs a new calculation pass to re-compute cells that use the cell with the reference to the asynchronous function.

Volatile and Non-Volatile Functions

Open Excel Mac Manual Calculation Mode 2017

Excel supports the concept of a volatile function, that is, one whose value cannot be assumed to be the same from one moment to the next even if none of its arguments (if it takes any) has changed. Excel reevaluates cells that contain volatile functions, together with all dependents, every time that it recalculates. For this reason, too much reliance on volatile functions can make recalculation times slow. Use them sparingly.

The following Excel functions are volatile:

NOW

TODAY

RANDBETWEEN

OFFSET

INDIRECT

INFO (depending on its arguments)

CELL (depending on its arguments)

SUMIF (depending on its arguments)

Both the VBA and C API support ways to inform Excel that a user-defined function (UDF) should be handled as volatile. By using VBA, the UDF is declared as volatile as follows.

By default, Excel assumes that VBA UDFs are not volatile. Excel only learns that a UDF is volatile when it first calls it. A volatile UDF can be changed back to non-volatile as in this example.

Using the C API, you can register an XLL function as volatile before its first call. It also enables you to switch on and off the volatile status of a worksheet function.

By default, Excel handles XLL UDFs that take range arguments and that are declared as macro-sheet equivalents as volatile. You can turn this default state off using the xlfVolatile function when the UDF is first called.

Calculation Modes, Commands, Selective Recalculation, and Data Tables

Excel has three calculation modes:

Automatic

Automatic Except Tables

Manual

When calculation is set to automatic, recalculation occurs after every data input and after certain events such as the examples given in the previous section. For very large workbooks, recalculation time might be so long that users must limit when this happens, that is, only recalculating when they need to. To enable this, Excel supports the manual mode. The user can select the mode through the Excel menu system, or programmatically using VBA, COM, or the C API.

Data tables are special structures in a worksheet. First, the user sets up the calculation of a result on a worksheet. This depends on one or two key changeable inputs and other parameters. The user can then create a table of results for a set of values for one or both of the key inputs. The table is created by using the Data Table Wizard. After the table is set up, Excel plugs the inputs one-by-one into the calculation and copies the resulting value into the table. As one or two inputs can be used, data tables can be one- or two-dimensional.

Recalculation of data tables is handled slightly differently:

Recalculation is handled asynchronously to regular workbook recalculation so that large tables might take longer to recalculate than the rest of the workbook.

Circular references are tolerated. If the calculation that is used to get the result depends on one or more values from the data table, Excel does not return an error for the circular dependency.

Data tables do not use multi-threaded calculation.

Given the different way that Excel handles recalculation of data tables, and the fact that large tables that depend on complex or lengthy calculations can take a long time to calculate, Excel lets you disable the automatic calculation of data tables. To do this, set the calculation mode to Automatic except Data Tables. When calculation is in this mode, the user recalculates the data tables by pressing F9 or some equivalent programmatic operation.

Excel exposes methods through which you can alter the recalculation mode and control recalculation. These methods have been improved from version to version to allow for finer control. The capabilities of the C API in this regard reflect those that were available in Excel version 5, and so do not give you the same control that you have using VBA in more recent versions.

Most frequently used when Excel is in manual calculation mode, these methods allow selective calculation of workbooks, worksheets, and ranges, complete recalculation of all open workbooks, and even complete rebuild of the dependency tree and calculation chain.

Range Calculation

Keystroke: None

VBA: Range.Calculate (introduced in Excel 2000, changed in Excel 2007) and Range.CalculateRowMajorOrder (introduced in Excel 2007)

C API: Not supported

Manual mode

Recalculates just the cells in the given range regardless of whether they are dirty or not. Behavior of the Range.Calculate method changed in Excel 2007; however, the old behavior is still supported by the Range.CalculateRowMajorOrder method.

Automatic or Automatic Except Tables modes

Recalculates the workbook but does not force recalculation of the range or any cells in the range.

Active Worksheet Calculation

Keystroke: SHIFT+F9

VBA: ActiveSheet.Calculate

C API: xlcCalculateDocument

All modes

Recalculates the cells marked for calculation in the active worksheet only.

Specified Worksheet Calculation

Keystroke: None

VBA: **Worksheets(**reference ).Calculate

C API: Not supported

All modes

Recalculates the dirty cells and their dependents within the specified worksheet only. Reference is the name of the worksheet as a string or the index number in the relevant workbook.

Excel 2000 and later versions expose a Boolean worksheet property, the EnableCalculation property. Setting this to True from False dirties all cells in the specified worksheet. In automatic modes, this also triggers a recalculation of the whole workbook.

In manual mode, the following code causes recalculation of the active sheet only.

Workbook Tree Rebuild and Forced Recalculation

Keystroke: CTRL+ALT+SHIFT+F9 (introduced in Excel 2002)

VBA: **Workbooks(**reference ).ForceFullCalculation (introduced in Excel 2007)

C API: Not supported

All modes

Causes Excel to rebuild the dependency tree and the calculation chain for a given workbook and forces a recalculation of all cells that contain formulas.

All Open Workbooks

Keystroke: F9

Excel Calculation Changes To Manual

VBA: Application.Calculate

C API: xlcCalculateNow

All modes

Recalculates all cells that Excel has marked as dirty, that is, dependents of volatile or changed data, and cells programmatically marked as dirty. If the calculation mode is Automatic Except Tables, this calculates those tables that require updating and also all volatile functions and their dependents.

All Open Workbooks Tree Rebuild and Forced Calculation

Keystroke: CTRL+ALT+F9

VBA: Application.CalculateFull

Macbook Manual

C API: Not supported

All modes

Recalculates all cells in all open workbooks. If the calculation mode is Automatic Except Tables, it forces the tables to be recalculated.